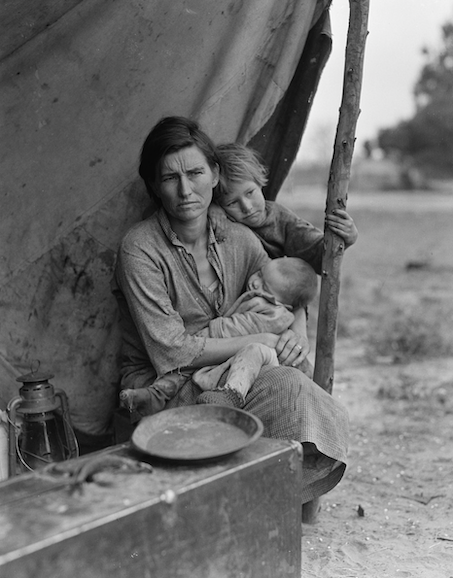

Dorothea Lange snapped her iconic “Migrant Mother” photo in 1936, the height of the Great Depression. In that photo, the mother, her face furrowed with worry, holds her infant; she supports two other young children leaning on her shoulders. Their faces are turned away from the camera. But here in this photo, we see another view, one that far fewer people have seen. The child at her mother’s shoulder now is more relaxed, more connected.

This woman in the photo was Florence Owens Thompson, 32-year-old mother of seven and of Cherokee descent. She became the face of an incredibly challenging era in American history. Her family was resting temporarily at a pea-pickers camp in California. You can see in this photo the makeshift tent they have assembled. It was here that Lange, employed by the Farm Security Administration, found Florence Owens Thompson and her children. The resulting series of photographs telegraphs hardship and endurance to the viewer.

Words, too, can go a long way toward connecting us with one another. Just as familiar as the subject of this photo are the many names from the Federal Writers’ Project (1936-40). Names like John Steinbeck, Zora Neale Hurston, and Eudora Welty. FWP was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s the Works Project Administration. The writers and photograpers were dispersed to document. This task was on par with other objectives of the program, like the building of national parks, bridges, and highways. Then there was the education of young men via the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), many of whom mailed their earnings back home to families otherwise destitute due to drought and famine.

For the FWP, people in cities and in the most remote corners of the country told these writers the stories of their everyday lives during the 1930s. They shared where they had come from. They described what kind of work they did. Some recounted the famous and not so famous people they had met. But why would this be such a crucial part of the WPA’s mission?

These life histories became a record of American life. That matters. FWP writers documented just what they heard and witnessed. Through their work, they preserved the stories of so-called every day people who, as the Migrant Mother photos illustrate, just may be extraordinary, too.

The Library of Congress’s page on the program offers a fascinating insight as to why the New Deal very intentionally included documenting these stories. “Most life histories were gathered under the direction of Benjamin A. Botkin, the folklore editor of the Writers’ Project. Like many intellectuals of his generation, Botkin was horrified at the rise of fascism in Europe and worried about possible consequences of that trend at home. By assembling occupationally and ethnically diverse life histories, he hoped to foster the tolerance necessary for a democratic, pluralistic community.”

There’s a reason that goes beyond even that one. It’s relevant to every decade, every generation. Most of life happens in our everyday moments, rather than the big events or even the selfie photos. That’s where we can find out what is most elemental in our lives. What we care about, how we live our lives, and what we remember can all be seen in the candid moments that too often go unnoticed. They can be found in the life histories — the stories — we perhaps too infrequently tell. But these stories can make a difference to the people who hear them, witness the unposed moment, or listen to the story or thought that only you can share. In Lange’s photo, the mother is taking what is probably a rare moment for repose and reflection, as we all need to do. What’s on your mind today? Who might you reach out to and share that story?

Photo source: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration.